Text encoding, code pages, UTF-8 and why ellipsis becomes “ÔǪ”

TLDR : Adding $OutputEncoding = [console]::OutputEncoding to your profile in PowerShell can avoid problems. But you need to know if it will cause others.

Note I originally wrote this after a discussion on github and there is some useful extra detail here. It has been waiting to get published for far too long

Basics

Most IT people know of ASCII - the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (and we’ll see shortly why “American” is important in that). It wasn’t the first attempt to map letters to binary patterns – telegraph did it in the late 1800, (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baudot_code ) using 5 bit codes – which gave 32 combinations; they didn’t use all zeros, and used 2 of the codes to switch between “letters” mode and “figures” mode, giving a total of 58 letters, digits, punctuation marks and control codes (like “Bell”, and “Carriage return”). The telegraph worked like a chord on piano, so E was easier to key than Q, ASCII saw the patterns as binary numbers and put things in sequence. It defined a working set of 127 characters, adding symbols and control codes, as well as Lower case letters. Today a space is represented by decimal 32 and the letter A by decimal 65 because that’s how the standards body defined them for ASCII. We run A, B, C…Z then a, b, c not Aa, Bb, Cc because ASCII says so.

One byte isn’t enough

ASCII uses one byte per character but didn’t define meanings for numbers 128-255 - vendors filled these in as they saw fit. Being American oriented the accented characters, and characters like Ð, ß, Å which are not used in English weren’t in the core 128 Nor are ¿ or £, used outside America. Even with these limitations, a huge proportion of text that circulates in the world can be handled as 7-bit ASCII.

As far back as MS-DOS in the 1980s it was clear that the 128 values not used by strict ASCII weren’t enough to handle all the different alphabets, symbols, and accented characters that a computer might need to display. The solution to this was “code pages”. If you loaded the code page for a non-Latin alphabet the high numbers could become Arabic, Cyrillic, Greek, or Hebrew characters, the European code page would give you extra accented characters and so on.

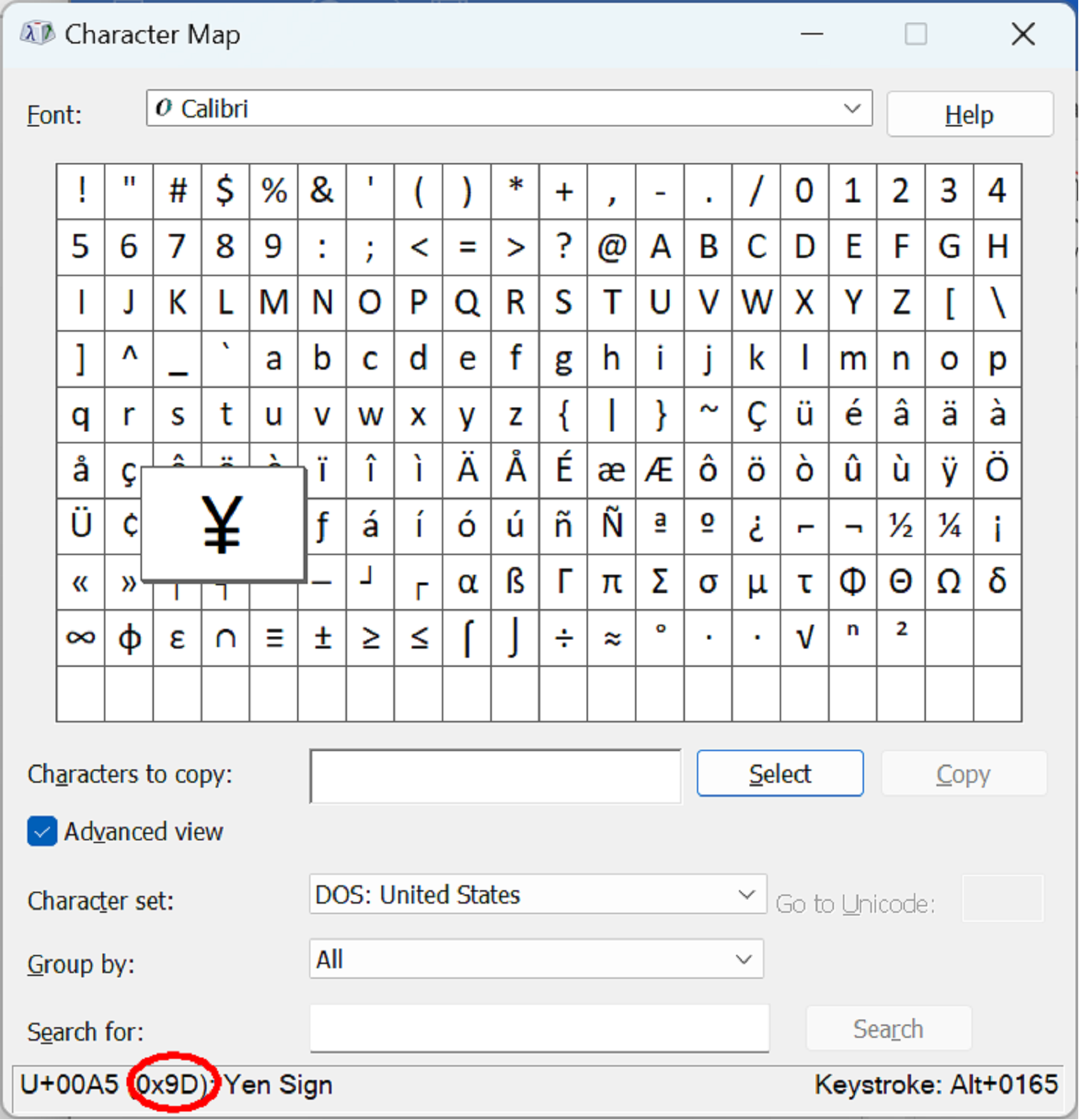

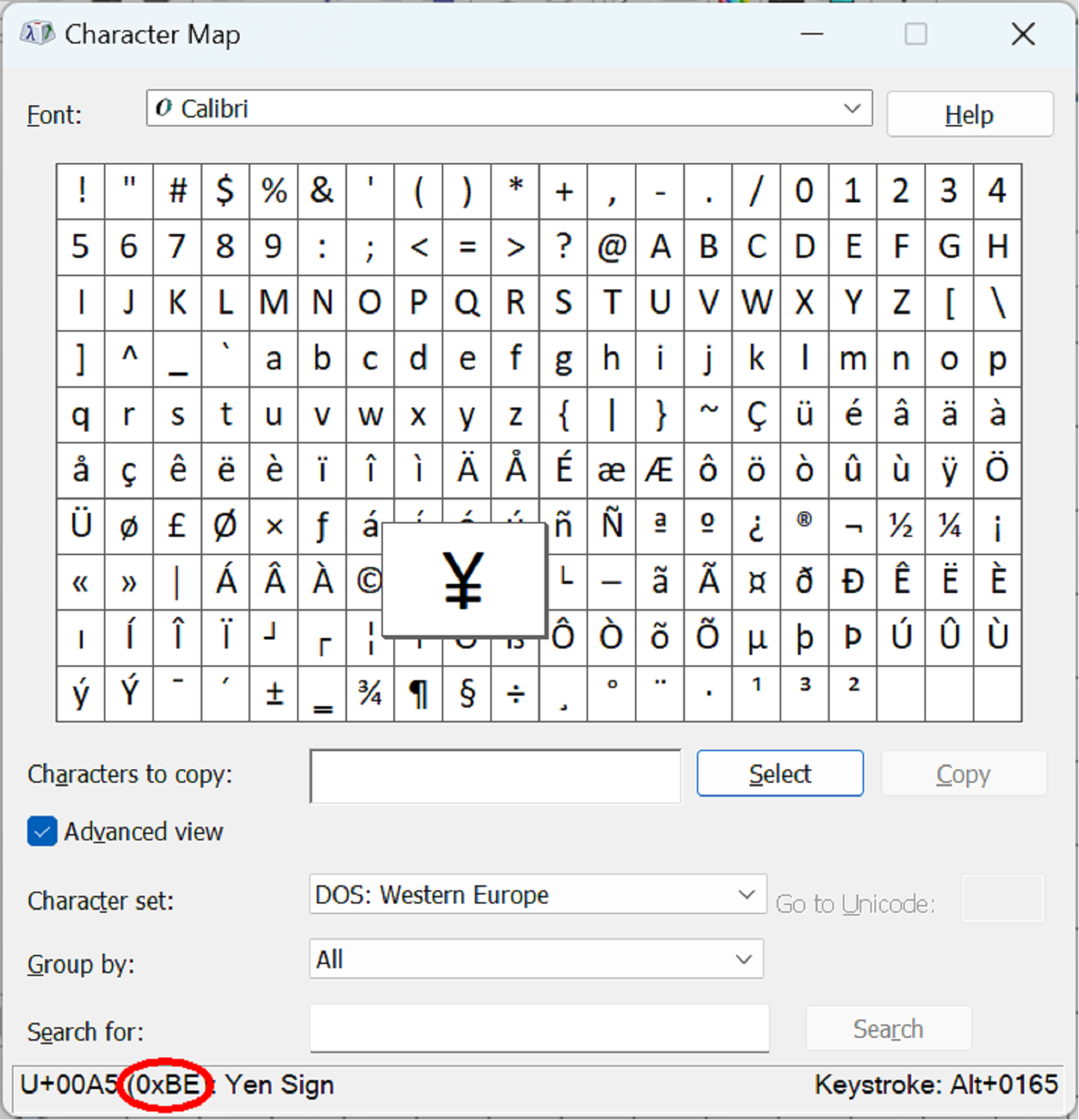

As the screen shots of Windows 11’s Character Map show, these 1980s code pages live on.

The top screen shot shows the US code page which includes π, (and other Greek letters used by mathematicians) and the bottom one shows the European one with the £ sign for pounds sterling, but no Pi – in the US the Yen sign is hex 9D (157 decimal) and in Europe in it is hex BE (190 decimal). If a file is written using one code page it must be read back using the same code page, otherwise the codes for £, π and ¥ take on other meanings.

Unicode

Unicode set out to solve the problem of only having 127 ASCII and 128 code-page defined characters available at a time. Initially it used two-byte encodings, but it can use longer ones – emojis use 3 bytes, and Unicode supports values from 0 to 10FFFF hex. In both the screen shots above, you can see the Yen sign is 00A5 (165 decimal) in Unicode and we can get this by holding ALT and typing 0165 on the numeric keypad (not the top row of the keyboard). 0-127 (007F in Hex) have the same meanings in Unicode as they do in ASCII, so space is still 32 decimal (0020 hex) and so on. Everything which previously appeared elsewhere in a code page should be somewhere in the 65536 characters supported by two-byte Unicode.

.NET and PowerShell use 16-bit characters for [char] and [string] types so

[char]0x2460 returns ① and so on. Previously, converting a number bigger

than 255 to a character would have given a “number too big” error. Unicode groups

characters so a regular expression to test for a letter like

“À” -match “\p{Lu}” (Lu means “Letter, Upper-case”) will return true but testing

for “À” -match “[A-Z]” returns false because the accented character lies outside the sequence.

By default, comparison, and therefore sorting, in .NET is culture aware and based on Unicode (so the sort

order of £, π and ¥ is consistent – π is a letter and sorts after z, £ and ¥ are

symbols and sort before a, upper and lower case act as tie-breaker between

identical terms).

However, writing 16 bits per character to a file would cause “Hello World” to

become the bytes

72 ,0, 101, 0, 108, 0, 108, 0, 111, 0, 32, 0, 87 0, 111, 0, 114, 0, 108, 0, 100, 0

and something expecting ASCII will treat that as “H e l l o w o r l d ” with

nulls after each character.

Fortunately, there is way to have both progress – allowing over 1 million characters (and overlaid parts like accents) – AND compatibility. This where the Unicode Transformation Formats (UTFs) come in.

We can write Unicode as blocks of four bytes (32 bits) known as UTF32 - this would allow us to write things like emojis directly - 00 01 F6 00 is a smiley face (see https://www.unicode.org/charts/#symbols for an index) but it is inefficient for normal text – hello world would start 72, 0, 0, 0, 101, 0, 0, 0, 108, 0, 0, 0 and – like the 16 bit versions - this won’t make sense to anything expecting 1-byte-per-character ASCII. But there is a more efficient way. In UTF-16 the numbers 0000-FFFF hex represent the characters (or parts of characters like accents – Unicode uses the term “code points” for each thing it encodes) but D800 to DFFF are reserved for encoding numbers greater than FFFF. We can see this in action in PowerShell.

PowerShell 6 introduced use the syntax "`u{xxxx}" to specify Unicode so

"`u{1F600}" gives the smiley face - this isn’t available in Windows PowerShell 5 where we need to use [System.Char]::ConvertFromUtf32(0x1F600)

We can split the result into single characters, and convert those to integers

and display them in hex format

PS> int[]][char[]]"`u{1F600}" | % {$_.tostring("x4")}

d83d

de00See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/UTF-16#Examples for how 0x1F600 is split, and how 0xD83D and 0xDE00 are recombined.

Using UTF-16 for strings in memory uses more space than than strictly necessary, but means conversions are only required rarely - for emojis, but not for symbols like the ellipsis character ( … ) or euro currency symbol ( € ). It also means that the length of the string in characters is (usually) the width of the output in characters (except when characters above 65535 need to be assembled from two stored characters, or when code parts work as overlays). But this doesn’t solve the problems of files expecting one-byte per character and being quite rigid about what the first 128 are used for.

A single byte encoding known as UTF-8 uses a similar transformation to the UTF-16 one above to encode values which need additional bits. In practice, values 0000-007F hex are written using one byte; anything between 0x0080 and 0x07FF (128 and 2,047 decimal) is split over two bytes, characters from 0800 to FFFF hex (2,048 to 65,535 decimal) are split over three bytes and those from 10000 to 10FFFF hex (65,536 to 2,097,151 decimal) use 4 bytes.

UTF 8: a 7-bit ASCII compatible way to write unicode

In UTF-8 numbers from 0 to 127 decimal have the same meanings as they do in

ASCII– so 7-bit ASCII text is unchanged when written as UTF-8. If a file doesn’t

have any characters outside the core 128, it can be read as ASCII (with any code

page) or as UTF-8. If the file uses a 16 or 32 bit encoding the first bytes in the

file tell whatever is reading it that it is UTF-16 or UTF-32 and whether the

bytes are in Big Endian or Little Endian order – this is known as Byte Order

Marking and there is a Byte Order Mark for UTF-8 but programs which expect ASCII

will treat this as content in the file, so it is usually omitted.

Bytes with values of 192 and above in UTF-8 mark the start of a larger Unicode

value (192-223 designates a two-byte character, 224-239 a three-byte one, and

240-247 is a four-byte one) and numbers between 128 and 191 are used for the additional bits. We can

see how A5 hex (165 decimal), the Unicode for the Yen sign, would be is

transformed into 8-bit format with this little piece of PowerShell:

PS> [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes([char]0xA5)

194

165

The two-byte format gives up to 11 bits, the first 5 are the least significant 5 bits of the first number, and the next 6 are the least significant 6 of the second; the three-byte format gives up to 16 bits, the first 4 are the least significant 4 of the first, followed by the least significant 6 of the second and third; and the four-byte format gives up to 21 bits: the least significant 3 of the first, and followed by the least significant 6 of the next three.

PS> [system.text.Encoding]::utF8.GetChars(@(194,165))

¥

does the translation to get back to the ¥ character. For a character like … (ellipsis)

PS> [int[]][char[]]"…"

8230

Tells us it is a Unicode character above 2048 so it will be 3 characters and we can see what these are in decimal or hex.

PS> [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes("…")

226

128

166

PS> [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes("…") | % {$_.tostring("x2")}

e2

80

a6

If we write these three bytes to a file, something which treats it as UTF 8 will translate them back to …, and this is what PowerShell 7 does. As we will see shortly the default encoding for file operations can be changed. Something which assumes ASCII + CodePage needs to use the correct code page; if there any bytes with values over 128 encoded in UTF-8 they will be misinterpreted, but this is no worse than having mismatched code pages.

Running Set-Content .\ellipsis.txt "…", followed byFormat-Hex -Path .\ellipsis.txt

in current versions of PowerShell shows the file contains

E2 80 A6 0D 0A

the three UTF-8 bytes for ellipsis, followed by carriage-return and line-feed (on Windows,

on other OSes it is ends with line feed).

In PowerShell type ellipsis.txt uses type as an alias for Get-Content which

defaults to assuming the file is UTF-8 and translates the 3 bytes back to “…”. But

in cmd things might not work so well:

cmd /c type .\\ellipsis.txt



In the “Western European” Code Page (850) which my machine (set for British English) uses by default, 0xE2 is “Capital O with circumflex”, 0x80 is “Capital C with Cedilla”, and 0xA6 is the “Feminine ordinal indicator” (in English we just have 1st for first but in Italian for example has 1º for primo and 1ª for prima).

We can see the available code pages and what the default is by running

Get-ItemProperty HKLM:\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Nls\CodePage\

If we change the code page to the US one (437) (which a machine set to US

English has by default) by running chcp 437 in cmd, the same type command

returns

…

This time 0xE2 is “Greek Capital Letter Gamma”, which still isn’t what we want.

A third common code page (sometimes called ANSI, for example in Notepad++ but

not an ANSI standard – it’s based on an ISO one) is the Windows 1252 code page

which renders differently again.

…

In this code page 0xE2 is “Latin small letter a with Circumflex”, 0x80 is “Euro sign” and 0xA6 is “broken bar” – on European keyboards this shares a key with back quote, it’s not the same as the | (0x7C) which usually shares a key with backslash.

These code pages (and there are others) can only present 256 characters, 128 standard ASCII ones, and 128 code-page specific ones, and only 1252 uses one of the latter for ellipsis (133 decimal, hex 85).

Fortunately, there is a code page for UTF-8, chcp 65001 selects it in cmd

and typing the 3-byte file will then give an ellipsis.

That’s four different code pages (850, 437, 1252, and 65001) and four different

interpretations of the same 3 bytes.

We can change the system code page in cmd either by running chcp in in a session

or by editing the “autoexec” at HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software\Microsoft\Command

Processor\Autorun and adding @chcp 65001 > nul

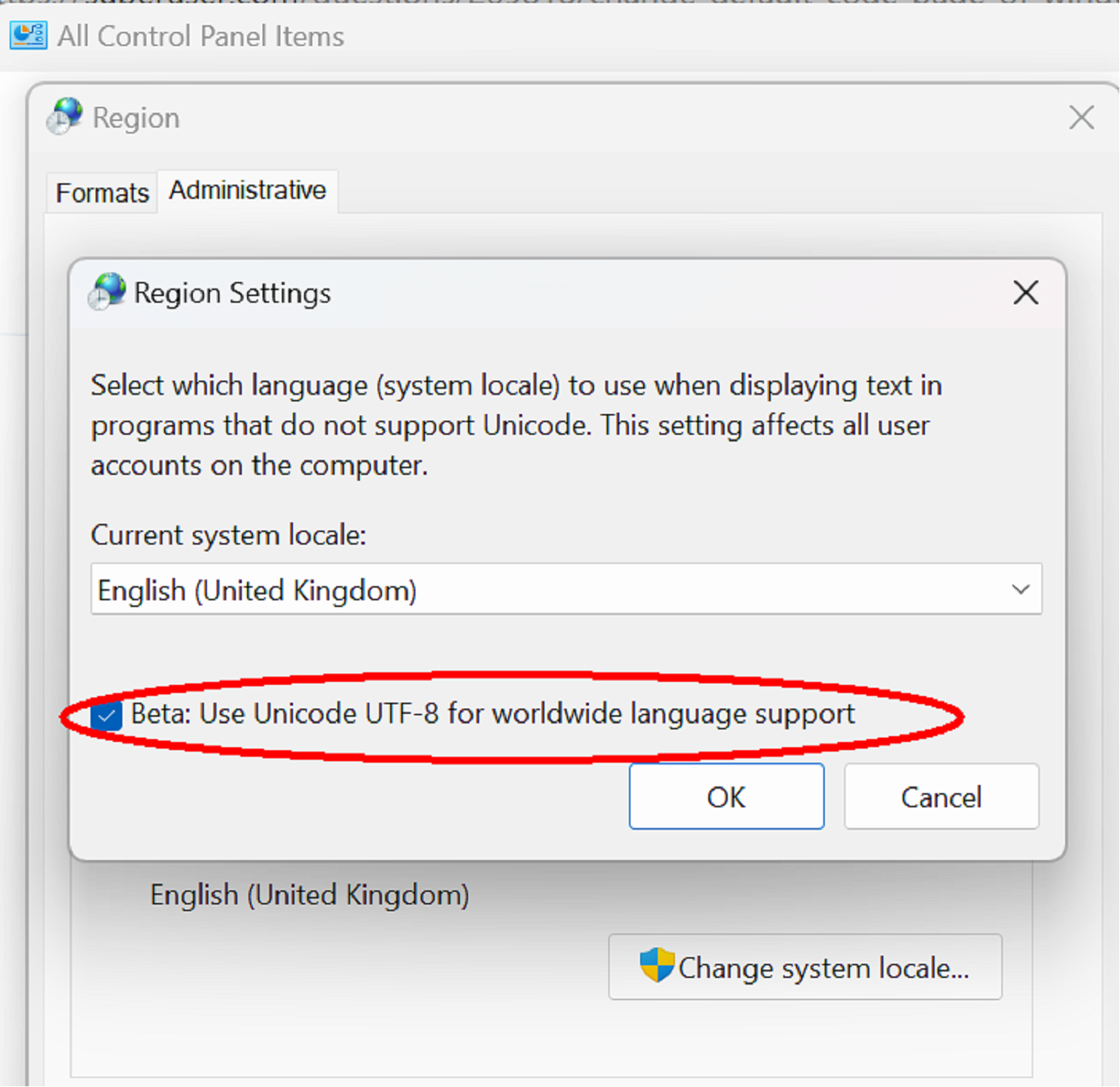

In Windows 11 and up-to-date versions of Windows 10, there is another option.

In Control Panel / Region / Administrative, changing the system locale has the option for UTF-8, so cmd and other tools will default to reading and writing UTF-8.

In PowerShell we can specify the encoding to read and write files the -Encoding

parameter - this can be can be different flavours of Unicode, including UTF-8 (with and without Byte Order Marks) -16 and -32 (the 16- and 32-bit versions can be in

big-endian or little-endian byte order) 7-bit ASCII, or “OEM” – the system code

page, it is also possible to select other code pages like this

PS> Get-Content .\ellipsis.txt -Encoding ([system.Text.Encoding]::getEncoding(437))

…

So: PowerShell can be told at the time it reads or writes the file what encoding to use for compatibility. If we know that whatever will read a PowerShell-created file assumes a particular encoding, then we can generate output accordingly. And if we know a file we must read uses a different encoding we can read it with the correct code page.

The preference variable $OutputEncoding tells Powershell how to encode data that it pipes into other

programs, so something like "…" | clip.exe might mean clip receives 0xE2 0x80

0xA6 if $OutputEncoding is UTF-8 or 0x85 if it is set to the 1252 code page.

If the code page is one which doesn’t have an ellipsis character it is replaced

with a “.”

If $OutputEncoding doesn’t match the default code page we might send the UTF8

representation and instead of the bytes translating back to “…”, code page 850 could tell

clip.exe to treat them as the single byte representations for

Capital O with circumflex, Capital C with Cedilla, Feminine ordinal indicator; meaning that,

when we paste we get “ÔǪ”. Code page 437 will mean pasting gives “ΓǪ”. The weird transformations

mentioned in the title are usually the result of a mismatch between sender’s and receiver’s codepages.

Fortunately, we can also see and/or change the active codepage for other programs we launch via [console]::outputEncoding.

The advice at the start that $OutputEncoding = [console]::OutputEncoding will fix many code

page oddities between PowerShell and external executables, works simply by ensuring that what PowerShell

sends matches the default. If we want to ensure that everything uses the same encoding there is

also [Console::]inputEncoding and changing Output but not input can cause some odd behaviour - the ideal is to use something like this:

$OutputEncoding = [console]::OutputEncoding = [console]::InputEncoding = [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8

to ensure the same codepage is used everywhere. If you know you will need some other code page select it, but if in doubt go for UTF-8. I’ve found fewer problems since I set the control panel option for it as well.