Maximize the reuse of your PowerShell

Last week I was at The Experts Conference in Frankfurt presenting at the PowerShell Deep Dive. My presentation was entitled “Maximize the reuse of your PowerShell”.

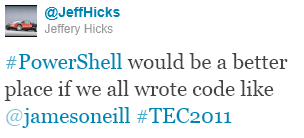

My PowerShell library for managing Hyper-V has now gone through a total of 100,000 downloads over all its different versions but whether it’s got wide use because of the way I wrote it or in spite of it, I can’t say. Some people whose views I value seem to agree with the ideas I put forward in the talk, so I’m setting them out in this (rather long) post

I have never lost my love of Lego. Like Lego, PowerShell succeeds by being a kit of small, general purpose blocks to link together. Not everything we do can extend that kit, but we should aim to do that where possible. I rediscovered the Monad Manifesto recently via a piece Jeffrey Snover wrote about how PowerShell has remained true to the original vision, named Monad. It talks of a model where “Every executable should do a narrow set of functions and complex functions should be composed by pipelining or sequencing executables together”. Your work is easier to reuse if it becomes a building block that can be incorporated into more complex solutions; and this certainly isn’t unique to PowerShell.

Functions for re-use, scripts for a single task. If you a use a .PS1 script to

carry out a task it is effectively a batch file: it is automating stuff so

that’s good, but it isn’t a building block for other work. Once loaded,

functions behave like compiled cmdlets. If you separate parts of a script into

functions it should be done with the aim of making those parts easy to reuse and

recycle, not simply be to reformat a script into subroutines.

If we’re going to write functions how should they look?

Choose names wisely, One task : One Function, there is no “DoStuffWith” verb

for a reason.

PowerShell cmdlets use names in the form Verb-Noun and it is best to stick to

this model; the Get-Verb command will give you a list of the Approved verbs.

PowerShell’s enforcement of these standards is limited to raising a warning if

you use non-standard names in a module. If your action really isn’t covered by a

standard verb, then log the need for another one on [edit:

GitHub ]; but if you use

“Duplicate” when the standard says “Copy”, or “Delete” when the standard says

“Remove” it simply makes things more difficult for people who know PowerShell

but don’t know your stuff. The same applies to parameter names: try to use the

ones people already know.

Getting the function name right sets the scope for your work. For my talk I used

an example of generating MD5 hashes for files. My assertion was that the MD5

hash belonged to the file, and so command should return a file with an added

MD5 hash – meaning my command should be Add-MD5.

Output: Use the right Out- and Write- cmdlets** Other speakers at the Deep

Dive made the point that output created with Write-Host isn’t truly returned (in

the sense that it can be piped or redirected) it is writing on the console

screen; so only use Write-Host if you want to prevent output going anywhere

else. There are other “write on the screen without returning” cmdlets which

might be better: for example, when debugging we often want messages that say,

“starting stage 1” , “starting stage 2” and so on. One way to do this would be

to add Write-Host statements and after the code is debugged remove them. A

better way is to use Write-Verbose which outputs if you specify a –verbose

switch and doesn’t if you don’t. As a side effect you have a quasi-comment in

your code which tells you what is happening. The same is true when you use

Write-Progress to indicate something is happening in a long running function,

(remember to run it with the -Completed switch when you have finished otherwise

your progress box can remain on screen while something else runs). Write-Debug,

Write-Error and Write-Warning are valuable, I try to prevent errors appearing

where the code can recover and write a warning when something didn’t go to plan,

in a non-fatal way.

Formatting results can be a thorny issue: you can redirect the results of

Format-Table or Format-List to a file, but the output is useless if you want to

pipe results into another command – which needs the original object.

Some objects can have ugly output: it’s not a crime to have an –AsTable switch

so output goes through Format-Table at the end of the function or even to

produce pretty output by default provided you ensure that it is possible to

get the raw object into the pipe with a –NoFormat or –Raw switch. But it’s

best to create formatting XML and a lot easier with tools like James

Brundage’s E-Z-out.

Output with the pipeline in mind. It’s not enough to just avoid write-host

and return some sort of object. I argued that a function should return the

richest object that is practical – my example used Add-Member to take a file

object and give it an additional MD5Hash property. I can do anything with the

result that I can do with a file and default formatting rules for a file are

used (which is usually good) but being the right type need not matter if the

object has the right property/properties. For example, this line of PowerShell :

Select-String -Path *.ps1 -Pattern "Select-String"

looks at all the .PS1 files in the current folder and where it finds the text

“Select-String” it outputs a MatchInfo object with the properties: .Context,

.Filename, .IgnoreCase, .Line, .LineNumber, .Matches, .Path and .Pattern. A

Cmdlet like Copy-Item has no idea about MatchInfo objects, but if an object

piped in has a .path property, it will know what it is being asked to work on.

If Matchinfo objects named this property “NameOfMatchingFile” it just would not

work.

Think about pipelined input. All it takes to tell PowerShell that a

parameter should come from the pipeline is prefixing its declaration with

[parameter(ValueFromPipeLine= $true)]

If you find that you are using your new function like this:

Get-thing | ForEach {Verb-Thing –thing $_}

It’s telling you that -thing should take pipeline values.

The pipeline can supply multiple items, so a function may need to be

split into begin{}, process{} and end{} blocks. (If you don’t specify these

the whole function body is treated as an end block and only the last item passed

is processed). Eventually the realization dawns that if the example above works,

it should be possible have two lines:

$t = Get-thing

Verb-Thing –thing $t

So, parameters need to be able to handle arrays – something I’ll come back to

further down. You can do the same thing that Copy-Item was shown doing above: I have another

function which is a wrapper for Select-String, its parameters include:

[Parameter(ValueFromPipeLine=$true,Mandatory=$true)]

$Pattern,

[parameter(ValueFromPipelineByPropertyName = $true)]

[Alias('Fullname','Path')]

$Include=@("*.ps1","*.js","*.sql")If the function gets passed a string via the pipeline it is the value for the

-Pattern parameter. If it gets an object containing a property named “Include”,

“Fullname” or “path” that property becomes the value for the –Include

parameter.

Sometimes a function needs change output destination based on input: so you can check to see if the destination parameter is a script block and evaluate it if it is.

Don’t require users to know syntax for things inside your function. If you

are going to write code to do one job and never reuse it then you don’t need to

be flexible. If the code is to be reused, you need to do a little extra work

so users don’t have to. For example: if something you use needs a fully

qualified path to a file, then the function should use Resolve-Path to avoid an

error when the user supplies the name of a file in the current directory.

Resolve-Path is quite content to resolve multiple items so replacing one line in

your function:

Do_stuff_with $path .

with

Resolve-Path $path | Foreach-Object {Do stuff with $_ }delivers, at a stroke, support for Wildcards, multiple items passed in $path

and relative names.

Another example is with WMI, where syntax is based on SQL so the wildcard is

“%”, not “*”. Users will assume the wildcard is *. In this case do you say:

(a) Users should learn to use “%”

(b) My function should include $parameter = $parameter -Replace "\*","%"

For my demo I showed a function I have named “Get-IndexedItem” which finds

things using the Windows index. I wanted to find my best underwater photos- they

are tagged “portfolio” and are the only photos I shoot with a Canon camera. My

function lets me type

Get-IndexedItem cameramaker=can*,tag=portfolio

Inside the function the search system needs a where condition of

“System.Photo.Cameramanufacturer LIKE 'can%' AND System.Keywords = 'portfolio‘” and some tools would require me to type the filtering condition in this form, but I

don’t want to remember what prefixes are needed and whether the names are

“camera Maker” or “camera Manufacturer” and “keyword”, “keywords” or “tag”. Half

the time I’ll forget to wrap things in single quotes, or use “*” as a wild card

because I forgot this was SQL. And if I have multiple search terms, why

shouldn’t they be a list instead of “A and B and C” (there is a write-up coming for how

I did this processing).

Set sensible defaults. The talk before mine highlighted some examples of “bad” coding and showed a function which accepted a computer name. Every time the user runs the command, they must specify the computer. Is it valid to assume that most of the time the command will run against the current computer? If so, the parameter should default to that. If the tool deals with files is it valid to assume “all files in the current directory” – if the command performs a deletion then, probably not, if it displays some aspect of the files, it probably can.

Constants could be Parameter defaults. With the computer name example, you might write a function which only ran against the current computer. Obviously, it is more useful if the computer name is a parameter (with a default) not a constant. In a surprising number of a cases, something you create to do a specific task can carry out a generic task if you change a fixed value in your code into a parameter, which defaults to the former fixed value.

Be flexible about parameter types and other validation This is a variation

on not making the user understand the internals of your function and I have

talked about it before, in particular the dangers of people who are trained

systems programmers applying the techniques in PowerShell they would use in

something like C#: in those languages a function declaration might look like:

single Circumference(single radius) {}

which says Circumference takes a parameter which must have been declared to be a

single precision real number and returns a single precision real number. Writing

c = Circumference("Hello");

or c = Circumference("42");

will cause the compiler to give a “type mismatch” error – “Hello” and “42” are

strings, not single precision real numbers . Similarly

System.io.fileinfo f = Circumference(42);

is a type mismatch: f is a fileInfo object and we can’t assign a number to it.

The compiler picks these things up before the program is ever run, so users

don’t see run-time errors.

PowerShell isn’t compiled and its function declarations don’t need a return type: Get-Item, for example, deals with the file system, certificate stores, the

registry etc. so it can return more than a dozen different types: there is no

way to know in advance what type of item Get-Item $y will return. If the result

is stored in a variable (with $x = Get-item $y ) the type of the variable

isn’t specified, but defined at runtime.

Trying to translate that declaration into PowerShell gives something like this.

function Get-Circumference{

Param([single]$Radius)

$radius * 2 * [system.math]::PI

}Calling Get-Circumference "Hello" produces an error but a closer inspection show it is not a type mismatch: it says

Cannot process argument transformation on parameter 'radius'. Cannot convert

value "hello" to type "System.Single".

the [Single] says “always try to cast $f as a single”. Which means

Get-Circumference "42"

will cast “42” from a string to a single and the function returns 263.89. There error wan’t that hello isn’t a single, it was that it could not be transformed into one.

You might expect

[System.IO.FileInfo]$f = Get-Circumference 42

to throw an error, but it doesn’t, PowerShell casts 263.893782901543 to an

object representing a file with that name in \windows\system32. The file

doesn’t exist and is read-only! So, it can be better to resolve types in

code.

I’d go further than that. Some validation is redundant because the parameter

will be passed to a cmdlet which is more flexible than the function-writer

thought, in other cases parameter validation is there to cover up a

programmer’s laziness. When I see a web site which demands that I don’t enter

spaces in my credit card number I think “Lazy. It’s easy to strip spaces and

dashes”. Having “O’Neill” for a surname means that the work of slovenly

developers who don’t check their SQL inputs or demand only-letters gets drawn to

my attention too. If the user is forced to use the equivalent of

Stop-Process (get-process Calc)

they will think “Lazy. you couldn’t be bothered even to provide a –Name

parameter”. Stop-process does just that to cope with process objects, names and

IDs (and notice it allows you to pass more than one ID) for example:

Stop-Process [-id ] 4472,5200,5224

$p = get-process calc ; Stop-Process -InputObject $p

Stop-Process -name calc

Other cmdlets are able to resolve types without using different parameters for

example

ren '.\\100 Meter Event.txt' "100 Metre Event.txt"

$f = get-item '.\\100 Metre Event.txt'

ren $f '100 Meter Event.txt'

In one case the first item is a string and in the other it is a file object: from a

user’s point of view this is better than Stop-Process which in turn is much

better than having to get an object representing the process you want to stop.

In my talk I used Set-VMMemory from my Hyper-V module on

Codeplex, which has:

param(

[parameter(ValueFromPipeLine = $true)]

$VM,

[Alias("MemoryInBytes")]

[long]$Memory = 0 ,

$Server = "."

)There isn’t a way for me to work out what a user means if they specify a memory size which isn’t a number (and can’t be cast to one). If the user specifies many Virtual Machines, catching something during parameter validation will produce one error instead of one per VM (so this would be the place to trap negative numbers too).

I have a –server parameter and it makes sense to assume the local machine – but

I can’t make an assumption about which VM(s) the user might want to modify. The

VM can come from the pipeline, and it might be an object which represents a VM,

or a string with a VM name (possibly a wildcard) or an array of VM objects

and/or Names. If the user says

Set-VMMemory –memory 1GB –vm london* –server h1,h2

then the function, not the user, translates that into the necessary objects. If this

doesn’t match any VMs I don’t want things to break. (Though I might produce a

warning). It takes 4 lines to support all of this

if ($VM -is [String]) { $VM = Get-VM -Name $VM -Server $Server}

if ($VM.count -gt 1 ) {

[Void]$PSBoundParameters.Remove("VM")

$VM | ForEach-object {Set-VMMemory -VM $_ @PSBoundParameters}

}

if ($vm.__CLASS -eq 'Msvm_ComputerSystem') {

do the main part of the code

}Incidentally, I use the __CLASS property because it works with remoting when

other methods for checking a WMI type failed.

Allow parts to be switched off. In the talk I explained I have a script

which applies new builds of software to a remote host. It does a backup and

creates a roll back script. Sometimes I have to roll back, produce another build

and then apply that. Since I have an up to date backup I don’t need to run the

backup a second time so that part of the code runs unless I specify a –nobackup

switch.

Support –WhatIf or restore data. You choose. A function can use

$pscmdlet.ShouldProcess – which returns true if the function should proceed

into a danger zone and false if it shouldn’t. It only takes one line line before

declaring the parameters at the start of a function to enable this

[CmdletBinding(SupportsShouldProcess=$true, ConfirmImpact='High' )]

There are 4 confirmation levels “None”, “Low”, “Medium,”, “High”, and for the

Confirm impact value and the $Confirmation preference variable. If either is

set to “None” no confirmation appears. If the impact level is higher or equal to

the preference setting this line

if ($pscmdlet.shouldProcess($file.name,”Delete file”) {Remove-item $file}

will delete the file or not depending on the users response to a prompt – in

this case “Performing operation “Delete File” on Target “filename”. Confirmation

can be forced on by specifying –Confirm. Specifying –WhatIf will echo the

message but return false. If no confirmation is needed, –verbose will echo the message but return true.

Prepare your code for other people, including you. I’m not the person I was a year ago. You’re not either, and we’ll be different people in 3 or 6 months. So even if you are not publishing your work, you are writing for someone else: you, in 3 months’ time, or You under-pressure at 3 in the morning. And that you will curse the you of today if leave your code in a mess.

There are many ways to format your code: find a style of indenting that works

for you, if it does, then the chances that anyone else will like it are about

the same as the chance they will hate it. Some people like to play “PowerShell

Golf” where fewest [key]strokes wins – this is fine for the command prompt.

Expanding things to make them easier to read is generally good. That’s not an

absolute ban on aliases – using Sort and Where instead of Sort-Object and

Where-Object may help readability – the key is to break up very long lines, but

without creating so many short lines that you are constantly scrolling up and

down.

Everyone says, “Put in brief comments”, but I’d refine that: explain WHY not

WHAT, for example I only decided to use Set-VMMemory as an example in my talk at

the last moment. It has a line

if (-not ($memory % 2mb)) {$memory /= 1mb}

I can’t have looked code in 8 months. Why would I do that ? Fortunately I’ve put in WHY comment – the WHAT is self-explanatory

# The API takes the amount of memory in MB, in multiples of 2MB.

# Assume that anything less than 2097152 is in already MB (we aren't assigning

2TB to the VM). If user enters 1024MB or 0.5GB divide by 1MB

Instead of putting comments next to each parameter saying what it does, move the comments into comment based help, take a couple of places where you have used / tested the command and put them into the comment based help as examples. Your future self will thank you for it.